Last week, we read about the albatross, especially the bird's appearance in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. You may remember that I posted an engraving of the albatross from that poem by Gustave Doré. That reminded me that I've been meaning to do an entry for a long time about Doré. Because this guy is The Man when it comes to engravings.

This is from the beginning of Paradise Lost. Satan has just woken up, discovered he's not in heaven anymore but rather has fallen into some burning lake, and he's talking to his old pal Beelzebub (standing, looking dire), with whom he recently fought a war against God and lost. They're just about to hatch their plan to round up the other fallen angels and keep the fight going on earth.

(Engraving by Gustave Doré, of course, sourced from Art Passions)

His engravings are incredible. Tempestuous, chock full of detail, passionate as the day is long -- and he made a ton of them.

I've always meant to find out more about him. So now is the time.

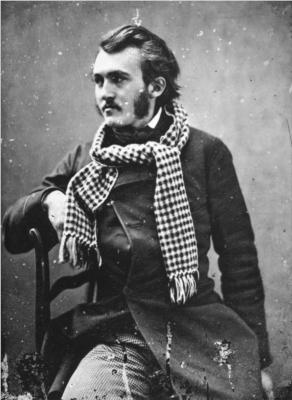

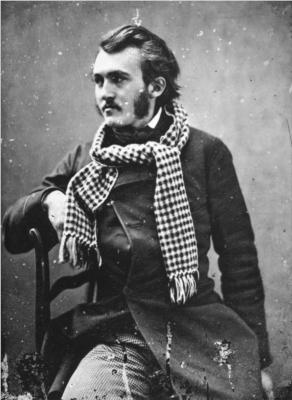

Young Gustave Doré

(Photo by Félix Nadar, sourced from WikiArt)

One of Doré's multitudinous caricatures. These are opera singers. His caption was, "People who sing opera generate huge acoustic forces."

(Drawing by Doré, sourced from Prospect magazine)

From Dante's Inferno, this is Paolo & Francesca being spotted by Dante & Virgil.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced originally from A Lonely Philosopher (the page no longer exists), subsequently picked up by GoPixPic)

Copper engravers also had to make mirror images of the thing they were engraving. Here, the engraver is shown with the print propped up next to him and a mirror in front of him. He is working from the mirror image of the design he wants to re-create on copper plate.

(Image from Steve Bartnick Antique Prints & Maps)

This is the famous engraving of Satan falling, from Paradise Lost. Hopefully this is large enough for you to see the engraved lines going horizontally across the entire image. They are especially noticeable in the dark clouds at the top, and in the lighter clouds at the earth's surface below. Notice, too, how those horizontal lines continue across even as he's got shafts of light coming down diagonally through them. And then, of course, there's the outline of Satan's body and the delicate curve of his wings, and specificity of his toes.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from North Country Public Radio)

Vivien and Merlin, 1867. Even in color, Doré hasn't lost his flair for the dramatic, for intense variations in light and shadow, and his love of tall knobbly trees.

(Painting by Doré, sourced from The Art Tribune)

From The Raven, illustration corresponding with "Darkness there and Nothing more." How many times in horror movies have we seen malevolent spirits crouching where the hero can't see them?

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Art Passions)

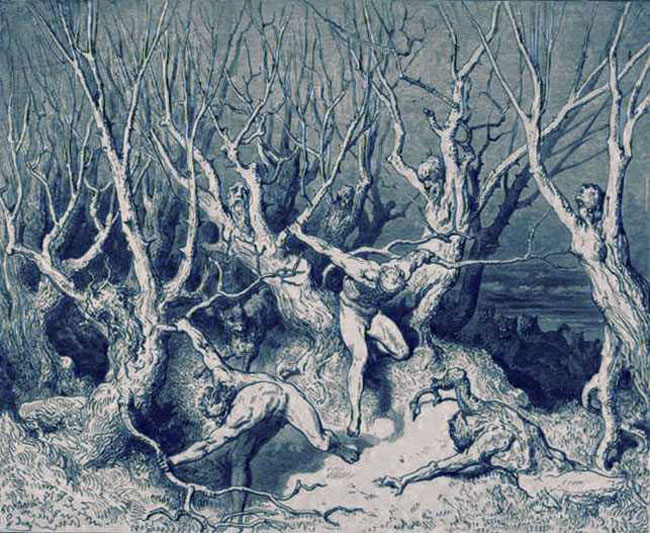

Spendthrifts running through the forest of suicides, from the Inferno. I think this just looks creepy.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from The World of Dante)

The Mariner, on board ship after the entire crew has died, "And yet I could not die." Neither have tales of ghost ships traveling the oceans.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Art Passions)

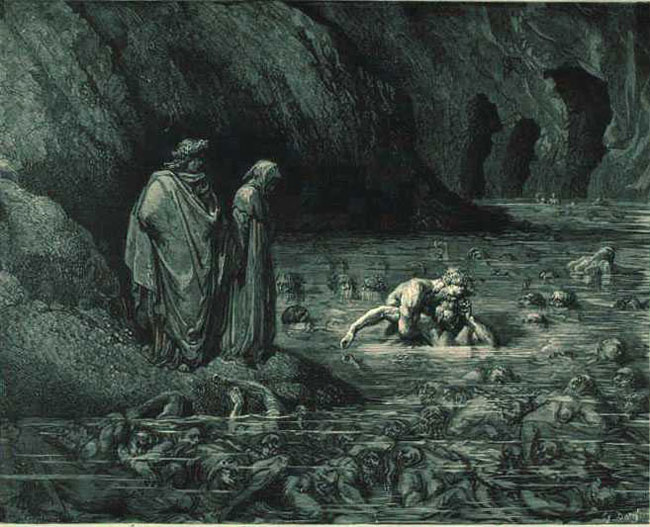

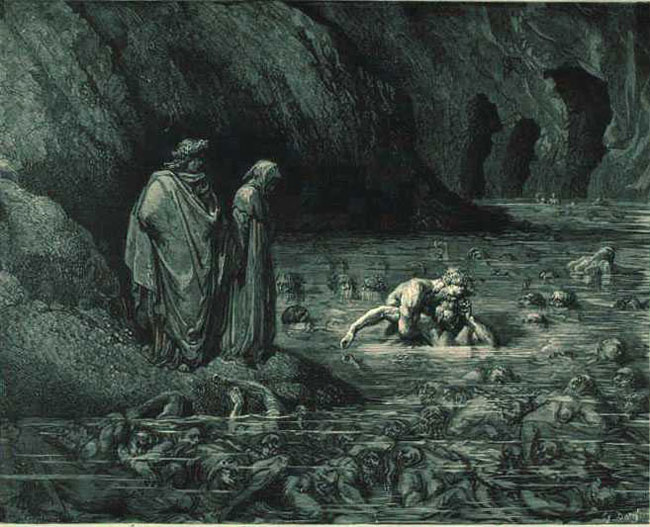

Ugolino, gnawing on the brains of Archbishop Ruggieri, from the Inferno. It doesn't get much more horrific than this. Maybe it's Dante who's to blame, more than Doré.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from The World of Dante)

Puss in Boots, looking as dramatic as Don Quixote.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Art Passions)

Sources

Gustave Doré

Yovisto Blog, The famous illustrations of Gustave Doré

Dan Malan, Gustave Doré - Adrift on Dreams of Splendor, at Postaprint

The World of Dante, Gustave Doré

Art Passions.net, Gustave Doré Art Collections

WikiArt, Gustave Doré

Charles Solomon, The son of King Kong and Gustave Doré / Ray Harryhausen discusses his influences for creating some of film's most memorable animation, SFGate, March 19, 2006

Katherine Stauble, Gustave Doré’s illustrious imagination, National Gallery of Canada Magazine, June 10, 2014

Engraving

Andy English, How Wood Engravings Are Made

Norman Kent, The Woodcut Versus the Wood Engraving

AIGA New Orleans, Know Your Design History: Metal versus wood engraving, April 24, 2014

The Collation from the Folger Shakespeare Library, Woodcut, engraving, or what? February 7, 2012

Steve Bartrick Antique Prints & Maps, Information - Printing Methods - Engraving

Thomas Ross Collection, The Art of the Engraver and Etcher

The Virtual Instructor.com, Hatching and Cross Hatching [sic]

expertvillage, Intaglio Print Engraving: Intaglio Print Crosshatching [video]

This is from the beginning of Paradise Lost. Satan has just woken up, discovered he's not in heaven anymore but rather has fallen into some burning lake, and he's talking to his old pal Beelzebub (standing, looking dire), with whom he recently fought a war against God and lost. They're just about to hatch their plan to round up the other fallen angels and keep the fight going on earth.

(Engraving by Gustave Doré, of course, sourced from Art Passions)

His engravings are incredible. Tempestuous, chock full of detail, passionate as the day is long -- and he made a ton of them.

I've always meant to find out more about him. So now is the time.

Young Gustave Doré

(Photo by Félix Nadar, sourced from WikiArt)

- Gustave Doré's full name is Paul Gustave Louis Christophe Doré. But you can call him Doré.

- He was born in 1832, in Strasbourg. That's in Alsace-Lorraine, which is that part of Europe which is kind of French, kind of German. He spent most of his life in Paris, though.

- He was the son of a wealthy engineer (seems like a contradiction in terms for the times), and he was extremely quick on the uptake in all sorts of things.

- His earliest known drawings were ones he made when he was 5. At 12, he carved his own set of lithographic stones, complete with companion stories for each. By 15, he was doing caricatures and drawings.

- While on a trip to Paris with his parents, they passed the window of a publisher where some illustrations were displayed. He pretended to be sick, told his family to go on without him, got out his sketchbook and made his own versions of the illustrations in the window. Then he went inside, set his illustrations on the publisher's desk, and said, "This is how those illustrations should be done."

- The publisher thought this kid was rather full of himself, but all the same he was stunned at the skill of the drawings. Skeptical that this kid who looked about 10 could have drawn so well, he asked the kid to make some more on the spot. So he did, in seconds.

- The publisher--Charles Philipon was his name--was so impressed, he would not allow Doré to leave his office. He had someone find Doré's parents and offered Gustave a contract then and there, for the next 3 years.

- So Doré moved in with the publisher, and Paris became his new home that day. By the following year, he had become one of the highest paid illustrators in the country.

- He became famous as the "boy genius," and published a book at the age of 16. He wrote all the text and did his own illustrations, some of them engraved in stone.

- Over the course of his teen years, he drew some 2,000 caricatures. That's about 500 caricatures per year.

One of Doré's multitudinous caricatures. These are opera singers. His caption was, "People who sing opera generate huge acoustic forces."

(Drawing by Doré, sourced from Prospect magazine)

- He soon became restless and began doing engraved illustrations for literary works -- all sorts of them.

- Such restlessness and the desire to keep working on the next project, and the next project, stayed with him throughout his life. In addition to caricatures and engravings, he would also produce his own books, paintings, and sculptures.

- But he remains best-known for his engravings. So let's talk about those for a while.

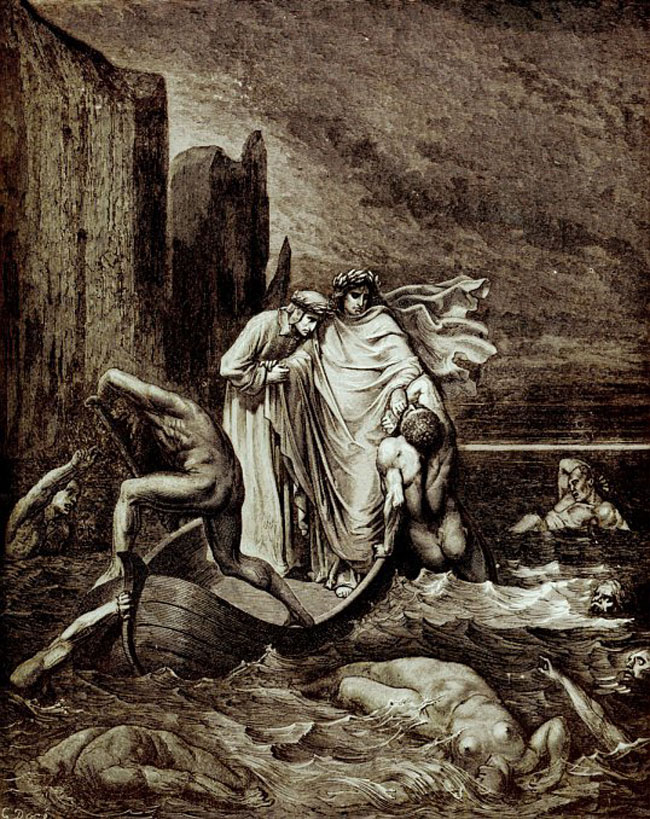

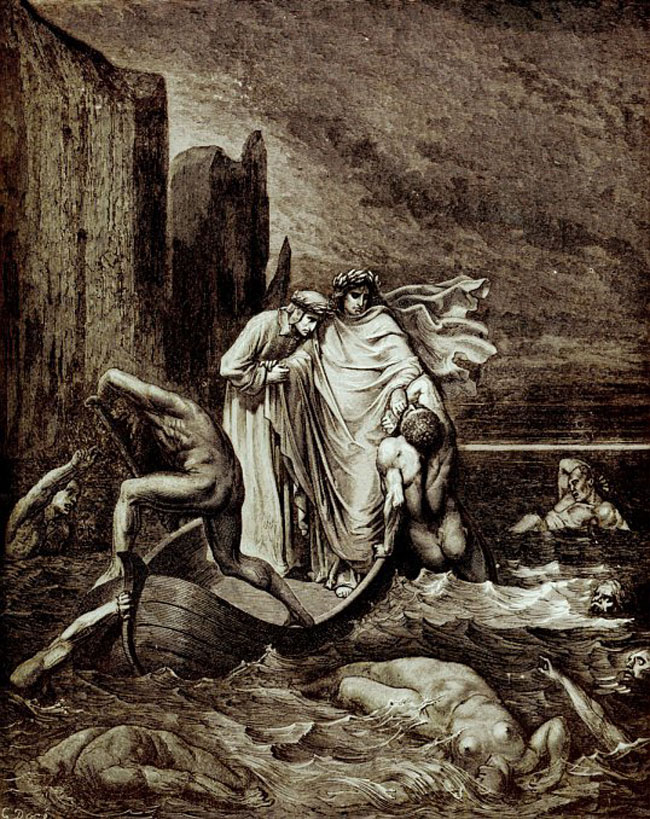

From Dante's Inferno, this is Paolo & Francesca being spotted by Dante & Virgil.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced originally from A Lonely Philosopher (the page no longer exists), subsequently picked up by GoPixPic)

- His first real engravings project was when he decided he wanted to make an illustrated version of Dante's Inferno. Folio-sized, meaning it would be enormous. And therefore pricey.

- The publisher, Hachette -- yes, the ones now fighting with Amazon -- thought this would never sell, so they didn't want to do it.

- Doré went ahead with it anyway. He made 76 full-page engraved illustrations, and he paid all the costs to have the book printed. Reluctantly, Hachette agreed to bind and sell the thing, but they made only 100 copies.

- Within only a few weeks, Doré received a telegram from Hachette saying, "Success! Come quickly! I am an ass!" (when does anyone get such a note from their publisher?) The Inferno had sold way more than the 100 copies almost immediately, and the book went into multiple reprintings. It has since been produced in over 200 editions.

- After that, Doré could provide engraved illustrations for pretty much any book he wanted to. The list of books he illustrated is pretty staggering. Here is an incomplete list:

- Dante's Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso

- The Bible

- Don Quixote

- Rabelais' complete works

- Perrault's Fairy Tales

- Baron Münchhausen (yes, Terry Gilliam got most of his ideas from Doré's illustrations)

- Arabian Nights

- Orlando Furioso

- History of the Crusades

- London: A Pilgrimage (social commentary)

- Balzac's Droll Stories

- Shakespeare's The Tempest

- Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner

- Tennyson's Idylls of the King

- Poe's The Raven

- Dickens' A Christmas Carol

While Dante clings to him, Virgil pushes Filippo Argenti back into the River Styx, who will be subsequently torn to pieces by the other wrathfuls in the Styx. Kind of remind of you of Inferii, don't they?

- Books are produced so quickly and easily today, you might be yawning and saying, "Eh, what's the big deal?" Let me show you what's the big deal.

- Below is a video showing how copper engravings were made, a little before Doré's time. He worked mainly with wood engravings, but all the videos that people have posted about how to make wood engravings show people using electric, modern-day tools. So while some of the processes involved in copper engraving are different than wood engraving, this gives you a pretty good sense of the amount of work involved in producing one engraving. One.

- The good stuff begins 36 seconds in.

- The guy in the video, Andrew, traces a drawing someone else made. Doré wouldn't have done that. He would have made his own drawing, and then made the engraving from there. In fact, he drew right on the material that would be engraved -- wood or metal. He didn't draw it on paper first.

- In copper engraving, you etch lines into the copper and the ink fills in the places you've gouged away. Excess ink is wiped off, as you see Andrew doing in the video. To get the ink to transfer onto paper, you have to use a ton of pressure to squeeze the ink out of the engraved channels onto the paper. That's why Andrew has to put the copper plate into a rolling press.

Copper engravers also had to make mirror images of the thing they were engraving. Here, the engraver is shown with the print propped up next to him and a mirror in front of him. He is working from the mirror image of the design he wants to re-create on copper plate.

(Image from Steve Bartnick Antique Prints & Maps)

- In wood engraving, you cut away the stuff you don't want, and the ink stays on the raised parts. No mirroring is necessary. The block is pressed to the paper, but it doesn't require the same kind of pressures that copper plates do. So wood engravings were relatively easier to print from.

- In about the 1820s, engravers figured out how to engrave on steel. Steel was much more durable than copper, and more impressions could be made from a steel plate than from a copper one. But since the material was firmer, it also required more force when being engraved.

- But steel's durability had another benefit, which was that it allowed the engravers to make extraordinarily fine lines very close together, without risking damaging the plate. As a result, steel engravings allowed for incredibly sharp detail, sharper than on copper or on wood. But to make such fine detail also required great intensity and focus by the engravers.

- Illustrators were having a great time making steel engravings, and the public were delighting in them. It was in this environment that Doré was making his wood and steel engravings.

- There's another part to how engravings are made that I want to point out. You'll notice that Doré's engravings are characterized by all sorts of fine lines running across the image. This is true of engravings in general. You don't ever really want to have any part of the plate unengraved. The ink would blob onto that smooth surface, and it wouldn't transfer very well to the paper. It would stick, and kind of suck at the paper as the paper was pulled away, and you'd get kind of a puckered impression.

- So you had to engrave everything, including the backgrounds. And you'd want to make the clouds distinct from the sky, or dark clouds distinct from light clouds, or a threatening sky distinct from the dark and scary mountainous peaks in the distance. So all of those things would require fine-line engraving, and each background element would have to be engraved slightly differently so as to distinguish one from the other.

This is the famous engraving of Satan falling, from Paradise Lost. Hopefully this is large enough for you to see the engraved lines going horizontally across the entire image. They are especially noticeable in the dark clouds at the top, and in the lighter clouds at the earth's surface below. Notice, too, how those horizontal lines continue across even as he's got shafts of light coming down diagonally through them. And then, of course, there's the outline of Satan's body and the delicate curve of his wings, and specificity of his toes.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from North Country Public Radio)

- Oh, and did I mention, the majority of Doré's engravings were done in wood, not steel? Paradise Lost was one of the books whose engravings he made on wood.

- So think about carving a million teeny tiny lines into a block of wood with a tool that looks something like this:

This is one wood engraver's tool, called a spitsticker. I am not kidding. It is similar to the copper engraver's burin, but here the handle is mushroom-shaped, as opposed to the burin's L-shaped handle. Your palm cups around the knob of the handle, and your thumb and forefinger grasp the top, dull part of the blade. The point of the blade is sharpened to a prism shape. It must be kept sharp throughout the engraving process, or you'll get ragged cuts in your surface.

(Drawing by Andy English)

- It is true that, later in Doré's career, he did have many apprentices working for him. He would draw the initial design, and his apprentices would do the finished engravings. As I mentioned earlier, he would draw directly onto the plate to be engraved, whether it was a disc of wood or a steel plate. The engravers would then follow his lines.

- But that said, his final tally is still impressive. Pretty much every major work of literature published in the late 1800s, Doré made engravings for it. His catalog totaled over 200 books, with multiple illustrations in each, some numbering over 400 plates per book.

- Just when he was hitting his peak of popularity, color printing started becoming the next big thing. It had been invented long before, but prints had to be colored by hand. But around this time, people were figuring out that you could carve wood cuts or engravings, one for each color, and print them sequentially to create a multi-colored print.

- People were wondering why Doré wasn't making any engravings that could be printed in color -- some have speculated that he was color blind. Whether it was to disprove his detractors or to try the next thing, he took up painting. The French said his paintings were really only illustrations in color, but others wondered why that was a problem.

- His paintings were shown at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1896 to an enormous turn-out. Over 16,000 people came to see the exhibit each day, totaling more than 1.5 million people in the 8 months it was at the museum. This broke every previous attendance record the museum had.

Vivien and Merlin, 1867. Even in color, Doré hasn't lost his flair for the dramatic, for intense variations in light and shadow, and his love of tall knobbly trees.

(Painting by Doré, sourced from The Art Tribune)

- But tastes in the art world were changing, away from the overly dramatic, and toward Impressionism, with less grandiose subjects, and a lot more color.

- So when Doré died in 1883, people were already looking ahead to the next thing in art and illustration.

- But Doré's influence remains. Some filmmakers say his illustrations "anticipated modern cinematography" for their use of dramatic light and shadow to highlight the central element in a composition, and they used some of his drawings as inspiration for composing their own scenes.

Doré's drawing of Baron Münchhausen

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Wikipedia)

Screenshot from The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (Anglicized spelling), brainchild of Terry Gilliam. Gilliam relied heavily on Doré's illustrations to decide what the characters in his movie should look like.

(Screenshot sourced from Morgan on Media)

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Wikipedia)

Screenshot from The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (Anglicized spelling), brainchild of Terry Gilliam. Gilliam relied heavily on Doré's illustrations to decide what the characters in his movie should look like.

(Screenshot sourced from Morgan on Media)

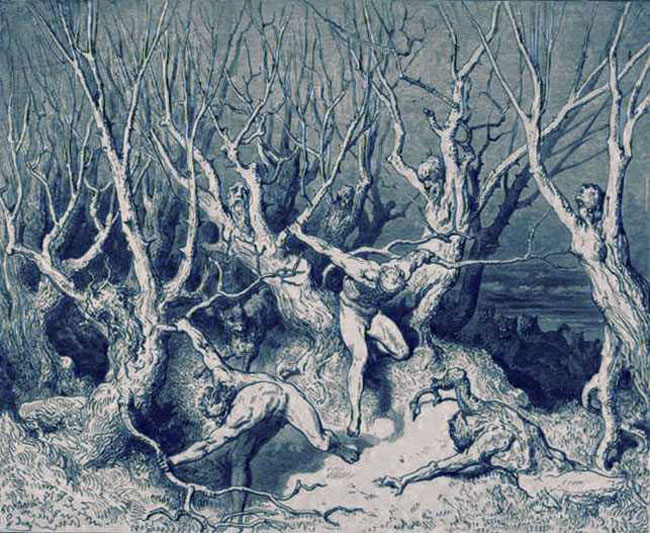

- Others in the field of literature say his illustrations marked the beginning of the horror genre -- particularly because of the engravings he made for The Raven. But I would argue his horror-friendly tendencies were present long before then.

From The Raven, illustration corresponding with "Darkness there and Nothing more." How many times in horror movies have we seen malevolent spirits crouching where the hero can't see them?

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Art Passions)

Spendthrifts running through the forest of suicides, from the Inferno. I think this just looks creepy.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from The World of Dante)

The Mariner, on board ship after the entire crew has died, "And yet I could not die." Neither have tales of ghost ships traveling the oceans.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Art Passions)

Ugolino, gnawing on the brains of Archbishop Ruggieri, from the Inferno. It doesn't get much more horrific than this. Maybe it's Dante who's to blame, more than Doré.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from The World of Dante)

- He is also considered to have contributed to the founding of comic books and graphic novels.

Puss in Boots, looking as dramatic as Don Quixote.

(Engraving by Doré, sourced from Art Passions)

- So his influence lives on, even if nobody makes 'em anymore the way he used to.

Sources

Gustave Doré

Yovisto Blog, The famous illustrations of Gustave Doré

Dan Malan, Gustave Doré - Adrift on Dreams of Splendor, at Postaprint

The World of Dante, Gustave Doré

Art Passions.net, Gustave Doré Art Collections

WikiArt, Gustave Doré

Charles Solomon, The son of King Kong and Gustave Doré / Ray Harryhausen discusses his influences for creating some of film's most memorable animation, SFGate, March 19, 2006

Katherine Stauble, Gustave Doré’s illustrious imagination, National Gallery of Canada Magazine, June 10, 2014

Engraving

Andy English, How Wood Engravings Are Made

Norman Kent, The Woodcut Versus the Wood Engraving

AIGA New Orleans, Know Your Design History: Metal versus wood engraving, April 24, 2014

The Collation from the Folger Shakespeare Library, Woodcut, engraving, or what? February 7, 2012

Steve Bartrick Antique Prints & Maps, Information - Printing Methods - Engraving

Thomas Ross Collection, The Art of the Engraver and Etcher

The Virtual Instructor.com, Hatching and Cross Hatching [sic]

expertvillage, Intaglio Print Engraving: Intaglio Print Crosshatching [video]

No comments:

Post a Comment

If you're a spammer, there's no point posting a comment. It will automatically get filtered out or deleted. Comments from real people, however, are always very welcome!